Water ice is likely to exist at the moon’s south pole, but it would be fragmented, scattered and buried deep beneath the surface, posing significant challenges for detection and extraction, according to a new study by Chinese researchers.

Using powerful Earth-based instruments, including the world’s largest radio telescope and one of the most advanced radar systems, the team estimated that ice made up no more than 6 per cent of the material within the top 10 metres (33 feet) of lunar soil in the region.

The ice was thought to exist as metre-sized chunks buried 5-7 metres underground in the moon’s most promising “cold traps”, known as permanently shadowed regions. Smaller, isolated patches might also lie near the surface, the team wrote in the latest issue of the Chinese journal, Science Bulletin.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

The findings, the researchers wrote, could help in the selection of landing sites for future lunar missions and inform the design of the proposed China-led research base on the moon.

Hu Sen, a planetary geochemist at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics in Beijing, called the work “impressive”. He said that using China’s newly built incoherent scatter radar in Sanya (SYISR) alongside the FAST telescope to search for water ice was a “really creative approach”.

While Hu was not involved in the research, he noted that the results aligned with previous impact experiment findings and added new evidence that water ice existed on the moon.

“The study also opened a new pathway to investigate water abundances on the moon,” he said.

So far, no liquid water has been found on the moon. “What we do know is that some water is bound within the lunar soil as ‘structural water’, and some is preserved as ice in cold traps inside permanently shadowed regions,” Hu said on Wednesday.

But the moon’s surface is an unforgiving environment, marked by a high vacuum, strong radiation and extreme temperature swings.

“Before anyone can actually make use of that water, we need to understand where it comes from, how it’s distributed and how it’s stored,” he said.

One of China’s key science goals for the coming Chang’e-7 mission, set to launch next year, is to determine the amount, origin and physical state of water ice at the moon’s south pole. The mission is expected to significantly advance understanding of lunar water, he said.

Still, the topic remains contentious. There is no conclusive proof that water ice exists in usable quantities on the moon. Alfred McEwen, a planetary geologist at Arizona State University, said he believed there was “extremely little” water on the moon.

“All the talk about what a valuable resource this is seems like baloney to me,” he said on Tuesday.

However, planetary geologist Clive Neal at the University of Notre Dame in the United States suggested that the actual amount of water ice at the lunar south pole could be higher than what this study detected.

Radar only covered limited areas, mostly crater slopes, he said.

“It is expected that the water ice would be in the bottom of the craters,” he said, adding that the areas visible to the radar were also affected by Earthshine, which could cause any surface ice to evaporate.

In recent years, researchers have paired high-powered, large-aperture incoherent scatter radars – typically used to study the ionosphere – with large radio telescopes to capture imagery of the moon’s surface, according to the paper’s lead author Li Mingyuan, of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics.

For instance, the Arecibo planetary radar system in Puerto Rico and the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia have jointly produced lunar polar images with resolution ranging from 20 to 150 metres, according to Li.

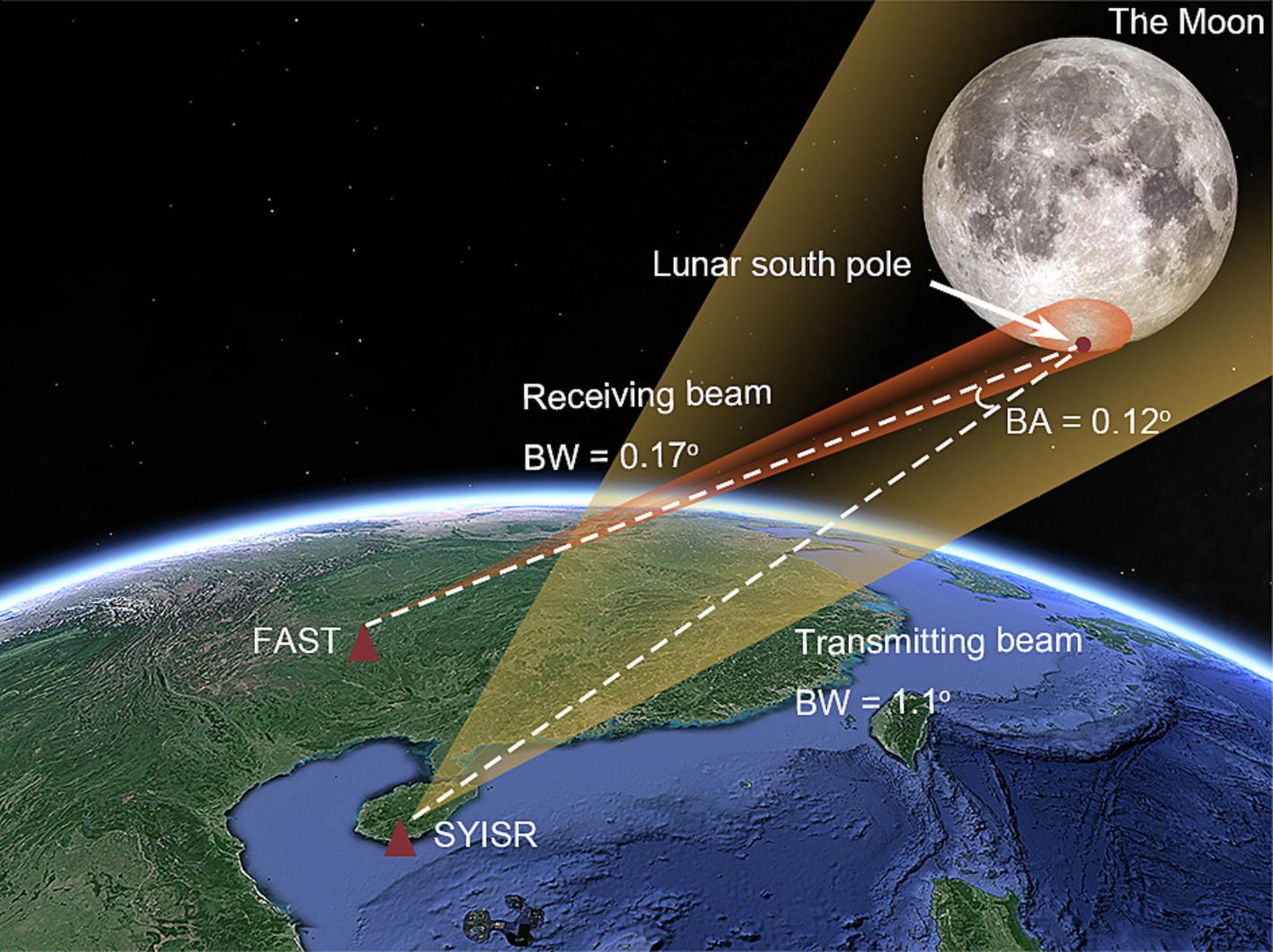

Building on that approach, Li and his team used the Sanya incoherent scatter radar and the Five-hundred-metre Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST) to carry out a ground-based radar imaging experiment focused on the moon’s south pole.

The SYISR radar, with its wide beam, was used to track the moon’s centre of mass and scan its entire near side. Meanwhile, the narrower beam of the FAST telescope focused specifically on the south pole region to receive radar echoes, he said.

Thanks to FAST’s high sensitivity, the team could produce radar images covering latitudes of 84 and 90 degrees south, at a resolution of about 500 metres by 1.2km.

Li noted that their analysis assumed the radar signals were caused by water ice. However, one of the key parameters – the circular polarisation ratio, which measures how much of the radar signal bounces back in a rotated form – can also be elevated by surface roughness or buried rocks, making it difficult to distinguish ice from non-ice terrain.

The study offered a preliminary estimate, Li said, and further work required integrating data from multiple instruments or radar frequencies to improve the accuracy of identifying water ice.

More from South China Morning Post:

- US space agency Nasa will not fund study on China’s moon sample: American scientist

- China’s daytime laser ranging breakthrough takes moon race to new heights

- US scientists given access to moon rocks brought back by China’s Chang’e-5 probe

- China’s moon shot: 2030 crewed lunar mission tests on pace, space agency says

- Brewing sake in space? Japanese maker aims for small step towards moon-based brewery

For the latest news from the South China Morning Post download our mobile app. Copyright 2025.